Home > Press > Ultra-thin nanowires can trap electron 'twisters' that disrupt superconductors

|

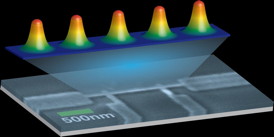

| This illustration depicts a short row of vortices held in place between the edges of a nanowire developed by Johns Hopkins scientists. CREDIT: Nina Markovic and Tyler Morgan-Wall/JHU |

Abstract:

Superconductor materials are prized for their ability to carry an electric current without resistance, but this valuable trait can be crippled or lost when electrons swirl into tiny tornado-like formations called vortices. These disruptive mini-twisters often form in the presence of magnetic fields, such as those produced by electric motors.

Ultra-thin nanowires can trap electron 'twisters' that disrupt superconductors

Baltimore, MD | Posted on February 24th, 2015To keep supercurrents flowing at top speed, Johns Hopkins scientists have figured out how to constrain troublesome vortices by trapping them within extremely short, ultra-thin nanowires. Their discovery was reported Feb. 18 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"We have found a way to control individual vortices to improve the performance of superconducting wires," said Nina Markovic, an associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

Many materials can become superconducting when cooled to a temperature of nearly 460 below zero F, which is achieved by using liquid helium.

The new method of maintaining resistance-free current within these superconductors is important because these materials play a key role in devices such MRI medical scanners, particle accelerators, photon detectors and the radio frequency filters used in cell phone systems. In addition, superconductors are expected to become critical components in future quantum computers, which will be able to do more complex calculations than current machines.

Wider use of superconductors may hinge on stopping the nanoscopic mischief that electron vortices cause when they skitter from side to side across a conducting material, spoiling the zero-resistance current. The Johns Hopkins scientists say their nanowires keep this from happening.

Markovic, who supervised the development of these wires, said other researchers have tried to keep vortices from disrupting a supercurrent by "pinning" the twisters to impurities in the conducting material, which renders them unable to move.

"Edges can also pin the vortices, but it is more difficult to pin the vortices in the bulk middle area of the material, farther away from the edges," she said. "To overcome this problem, we made a superconducting sample that consists mostly of edges: a very narrow aluminum nanowire."

These nanowires, Markovic said, are flat strips about one-billionth as wide as a human hair and about 50 to 100 times longer than their width. Each nanowire forms a one-way highway that allows pairs of electrons to zip ahead at a supercurrent pace.

Vortices can form when a magnetic field is applied, but because of the material's ultra-thin design, "only one short vortex row can fit within the nanowires," Markovic said. "Because there is an edge on each side of them, the vortices are trapped in place and the supercurrent can just slip around them, maintaining the resistance-free speed."

The ability to control the exact number of vortices in the nanowire may produce additional benefits, physics experts say. Future computers or other devices may someday use vortices instead of electrical charges to transmit information, they say.

###

The lead author of the Physical Review Letters article was Tyler Morgan-Wall, a doctoral student in Markovic's lab. Along with Markovic, the co-authors were Benjamin Leith, who was an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins when the research took place; Nikolaus Hartman, a graduate student; and Atikur Rahman, who was a postdoctoral fellow in Markovic's lab.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Phil Sneiderman

443-997-9907

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS

3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N-2600

Baltimore, MD 21211

Phone: 443-997-9009 / Fax: 443-997-1006

Copyright © Johns Hopkins University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Department of Physics and Astronomy:

Department of Physics and Astronomy:

![]() Krieger School of Arts and Sciences:

Krieger School of Arts and Sciences:

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Superconductivity

![]() MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

MXene nanomaterials enter a new dimension Multilayer nanomaterial: MXene flakes created at Drexel University show new promise as 1D scrolls January 30th, 2026

![]() Lattice-driven charge density wave fluctuations far above the transition temperature in Kagome superconductor April 25th, 2025

Lattice-driven charge density wave fluctuations far above the transition temperature in Kagome superconductor April 25th, 2025

Chip Technology

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

Beyond silicon: Electronics at the scale of a single molecule January 30th, 2026

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Nanoelectronics

![]() Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

Lab to industry: InSe wafer-scale breakthrough for future electronics August 8th, 2025

![]() Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

![]() Key element for a scalable quantum computer: Physicists from Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University demonstrate electron transport on a quantum chip September 23rd, 2022

Key element for a scalable quantum computer: Physicists from Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University demonstrate electron transport on a quantum chip September 23rd, 2022

![]() Reduced power consumption in semiconductor devices September 23rd, 2022

Reduced power consumption in semiconductor devices September 23rd, 2022

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Interviews/Book Reviews/Essays/Reports/Podcasts/Journals/White papers/Posters

![]() Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

Metasurfaces smooth light to boost magnetic sensing precision January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||