Home > Press > Chaperones for climate protection

|

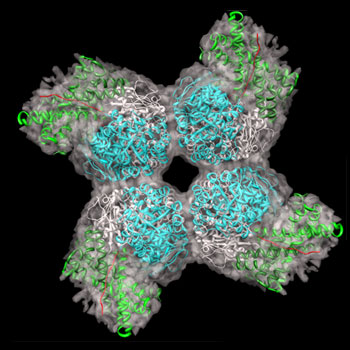

| Rubisco binds carbon dioxide and facilitates the conversion to sugar and oxygen. Image: Andreas Bracher / Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry |

Abstract:

The protein Rubisco locks up carbon dioxide / Biochemists synthesis Rubisco in the test tube for the first time

Chaperones for climate protection

Munich, Germany | Posted on January 16th, 2010The World Climate Conference recently took place. Reports about carbon dioxide levels, rising temperatures and melting glaciers appear daily. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) of Biochemistry and the Gene Center of Ludwig Maximilians University Munich have now succeeded in rebuilding the enzyme Rubisco, the key protein in carbon dioxide fixation. "Rubisco is one of the most important proteins on the planet, yet despite this, it is also one of the most inefficient", says Manajit Hayer-Hartl, a group leader at the MPI of Biochemistry. The researchers are now working on modifying the artificially produced Rubisco so that it will convert carbon dioxide more efficiently than the original protein. Their work has now been published in Nature (Nature, January 14, 2010).

Photosynthesis is one of the most important biological processes. Plants metabolize carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and sugar in the presence of light. Without this process, life on earth as we know it would not be possible. The key protein in photosynthesis, Rubisco, is thus one of the most important proteins in nature. It bonds with carbon dioxide and starts its conversion into sugar and oxygen. "But this process is really inefficient", explains Manajit Hayer-Hartl. "Rubisco not only reacts with carbon dioxide but also quite often with oxygen." This did not cause any problems with the protein developed three billion years ago. Back then, there was no oxygen present in the atmosphere. However, as more and more oxygen accumulated, Rubisco could not adjust to this change.

The protein Rubisco is a large complex consisting of 16 subunits. Up to now, its complex structure made it impossible to reconstruct Rubisco in the laboratory. To overcome this obstacle, scientists at the MPI of Biochemistry and at the Gene Center of the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich used the help of cellular chaperones. The French term chaperone describes a woman who accompanies a young lady to a date and takes care that the young gentleman will not approach her protégé improperly. The molecular chaperones within the cell work in a similar way: They ensure that only the correct parts of a newly synthesized protein will come together. As a result of this process, the protein acquires its correct three dimensional structure. "With 16 subunits like those of Rubisco, the risk is very high that the wrong parts of the protein clump together and form useless aggregates," says the biochemist. Only with its correct structure will Rubisco be able to fulfil its function in plants.

The MPI researchers showed that two different chaperone systems, called GroEL and RbcX, are necessary to produce a functional Rubisco complex. The next aim of the scientists is to genetically modify Rubisco so that it bonds with carbon dioxide more often and metabolizes oxygen less frequently. "Because the modified Rubisco is predicted to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere more effectively," says Manajit Hayer-Hartl, "it would enhance crop yields and could also be interesting for climate protection."

Related links:

[1] Chaperonin-assisted Protein Folding www.biochem.mpg.de/en/rg/hayer-hartl/

Original work:

C. Liu, A. L. Young, A. Starling-Windhof, A. Bracher, S. Saschenbrecker, B. Vasudeva Rao, K. Vasudeva Rao, O. Berninghausen, T. Mielke, F. U. Hartl, R. Beckmann and M. Hayer-Hartl

Coupled chaperone action

####

About Max Planck Society

The research institutes of the Max Planck Society perform basic research in the interest of the general public in the natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences, and the humanities. In particular, the Max Planck Society takes up new and innovative research areas that German universities are not in a position to accommodate or deal with adequately. These interdisciplinary research areas often do not fit into the university organization, or they require more funds for personnel and equipment than those available at universities. The variety of topics in the natural sciences and the humanities at Max Planck Institutes complement the work done at universities and other research facilities in important research fields. In certain areas, the institutes occupy key positions, while other institutes complement ongoing research. Moreover, some institutes perform service functions for research performed at universities by providing equipment and facilities to a wide range of scientists, such as telescopes, large-scale equipment, specialized libraries, and documentary resources.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Dr. Manajit Hayer-Hartl

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried

Anja Konschak, Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried

Tel.: +49 89 8578-2824

Copyright © Max Planck Society

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Possible Futures

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Discoveries

![]() From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

From sensors to smart systems: the rise of AI-driven photonic noses January 30th, 2026

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Announcements

![]() Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

Decoding hydrogen‑bond network of electrolyte for cryogenic durable aqueous zinc‑ion batteries January 30th, 2026

![]() COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

COF scaffold membrane with gate‑lane nanostructure for efficient Li+/Mg2+ separation January 30th, 2026

Food/Agriculture/Supplements

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

SMART researchers pioneer first-of-its-kind nanosensor for real-time iron detection in plants February 28th, 2025

![]() Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Silver nanoparticles: guaranteeing antimicrobial safe-tea November 17th, 2023

Environment

![]() Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

Researchers unveil a groundbreaking clay-based solution to capture carbon dioxide and combat climate change June 6th, 2025

![]() Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Onion-like nanoparticles found in aircraft exhaust May 14th, 2025

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

New molecular technology targets tumors and simultaneously silences two ‘undruggable’ cancer genes August 8th, 2025

![]() New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

New imaging approach transforms study of bacterial biofilms August 8th, 2025

![]() Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev researchers several steps closer to harnessing patient's own T-cells to fight off cancer June 6th, 2025

![]() Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

Electrifying results shed light on graphene foam as a potential material for lab grown cartilage June 6th, 2025

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||