Home > Press > Scientists Capture Ultrafast Snapshots of Light-Driven Superconductivity: X-rays reveal how rapidly vanishing 'charge stripes' may be behind laser-induced high-temperature superconductivity

|

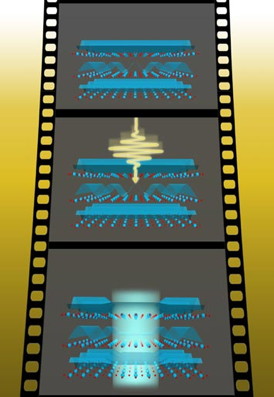

| In equilibrium (top), the charge stripe "ripples" run perpendicular to each other between the copper-oxide layers of the material. When a mid-infrared laser pulse strikes the material (middle), it "melts" these conflicting ripples and induces superconductivity (bottom). The experimenters used a carefully synchronized x-ray laser to take this femtosecond–fast "movie" to reveal how quickly the charge stripes melt. Image courtesy Jörg Harms, Max-Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter. |

Abstract:

A new study pins down a major factor behind the appearance of superconductivity-the ability to conduct electricity with 100 percent efficiency-in a promising copper-oxide material.

Scientists Capture Ultrafast Snapshots of Light-Driven Superconductivity: X-rays reveal how rapidly vanishing 'charge stripes' may be behind laser-induced high-temperature superconductivity

Upton, NY | Posted on April 16th, 2014Scientists used carefully timed pairs of laser pulses at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) to trigger superconductivity in the material and immediately take x-ray snapshots of its atomic and electronic structure as superconductivity emerged.

They discovered that so-called "charge stripes" of increased electrical charge melted away as superconductivity appeared. Further, the results help rule out the theory that shifts in the material's atomic lattice hinder the onset of superconductivity.

Armed with this new understanding, scientists may be able to develop new techniques to eliminate charge stripes and help pave the way for room-temperature superconductivity, often considered the holy grail of condensed matter physics. The demonstrated ability to rapidly switch between the insulating and superconducting states could also prove useful in advanced electronics and computation.

The results, from a collaboration led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Structure and Dynamics of Matter in Germany and the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC and Brookhaven national laboratories, were published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"The very short timescales and the need for high spatial resolution made this experiment extraordinarily challenging," said co-author Michael Först, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute. "Now, using femtosecond x-ray pulses, we found a way to capture the quadrillionths-of-a-second dynamics of the charges and the crystal lattice. We've broken new ground in understanding light-induced superconductivity."

Ripples in Quantum Sand

The compound used in this study was a layered material consisting of lanthanum, barium, copper, and oxygen grown at Brookhaven Lab by physicist Genda Gu. Each copper oxide layer contained the crucial charge stripes.

"Imagine these stripes as ripples frozen in the sand," said John Hill, a Brookhaven Lab physicist and coauthor on the study. "Each layer has all the ripples going in one direction, but in the neighboring layers they run crosswise. From above, this looks like strings in a pile of tennis racquets. We believe that this pattern prevents each layer from talking to the next, thus frustrating superconductivity."

To excite the material and push it into the superconducting phase, the scientists used mid-infrared laser pulses to "melt" those frozen ripples. These pulses had previously been shown to induce superconductivity in a related compound at a frigid 10 Kelvin (minus 442 degrees Fahrenheit).

"The charge stripes disappeared immediately," Hill said. "But specific distortions in the crystal lattice, which had been thought to stabilize these stripes, lingered much longer. This shows that only the charge stripes inhibit superconductivity."

Stroboscopic Snapshots

To capture these stripes in action, the collaboration turned to SLAC's LCLS x-ray laser, which works like a camera with a shutter speed faster than 100 femtoseconds, or quadrillionths of a second, and provides atomic-scale image resolution. LCLS uses a section of SLAC's 2-mile-long linear accelerator to generate the electrons that give off x-ray light.

"This represents a very important result in the field of superconductivity using LCLS," said Josh Turner, an LCLS staff scientist. "It demonstrates how we can unravel different types of complex mechanisms in superconductivity that have, up until now, been inseparable."

He added, "To make this measurement, we had to push the limits of our current capabilities. We had to measure a very weak, barely detectable signal with state-of-the-art detectors, and we had to tune the number of x-rays in each laser pulse to see the signal from the stripes without destroying the sample."

The researchers used the so-called "pump-probe" approach: an optical laser pulse strikes and excites the lattice (pump) and an ultrabright x-ray laser pulse is carefully synchronized to follow within femtoseconds and measure the lattice and stripe configurations (probe). Each round of tests results in some 20,000 x-ray snapshots of the changing lattice and charge stripes, a bit like a strobe light rapidly illuminating the process.

To measure the changes with high spatial resolution, the team used a technique called resonant soft x-ray diffraction. The LCLS x-rays strike and scatter off the crystal into the detector, carrying time-stamped signatures of the material's charge and lattice structure that the physicists then used to reconstruct the rise and fall of superconducting conditions.

"By carefully choosing a very particular x-ray energy, we are able to emphasize the scattering from the charge stripes," said Brookhaven Lab physicist Stuart Wilkins, another co-author on the study. "This allows us to single out a very weak signal from the background."

Toward Superior Superconductors

The x-ray scattering measurements revealed that the lattice distortion persists for more than 10 picoseconds (trillionths of a second)-long after the charge stripes melted and superconductivity appeared, which happened in less than 400 femtoseconds. Slight as it may sound, those extra trillionths of a second make a huge difference.

"The findings suggest that the relatively weak and long-lasting lattice shifts do not play an essential role in the presence of superconductivity," Hill said. "We can now narrow our focus on the stripes to further pin down the underlying mechanism and potentially engineer superior materials."

Andrea Cavalleri, Director of the Max Planck Institute, said, "Light-induced superconductivity was only recently discovered, and we're already seeing fascinating implications for understanding it and going to higher temperatures. In fact, we have observed the signature of light-induced superconductivity in materials all the way up to 300 Kelvin (80 degrees Fahrenheit)-that's really a significant breakthrough that warrants much deeper investigations."

Other collaborators on this research include the University of Groningen, the University of Oxford, Diamond Light Source, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Stanford University, the European XFEL, the University of Hamburg and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science.

The research conducted at the Soft X-ray Materials Science (SXR) experimental station at SLAC's LCLS-a DOE Office of Science user facility-was funded by Stanford University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the University of Hamburg, and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science (CFEL). Work performed at Brookhaven Lab was supported by the DOE's Office of Science.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

####

About Brookhaven National Laboratory

One of ten national laboratories overseen and primarily funded by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Brookhaven National Laboratory conducts research in the physical, biomedical, and environmental sciences, as well as in energy technologies and national security. Brookhaven Lab also builds and operates major scientific facilities available to university, industry and government researchers. Brookhaven is operated and managed for DOE's Office of Science by Brookhaven Science Associates, a limited-liability company founded by the Research Foundation for the State University of New York on behalf of Stony Brook University, the largest academic user of Laboratory facilities, and Battelle, a nonprofit, applied science and technology organization.

Visit Brookhaven Lab's electronic newsroom for links, news archives, graphics, and more at www.bnl.gov/newsroom, follow Brookhaven Lab on Twitter, twitter.com/BrookhavenLab, or find us on Facebook, www.facebook.com/BrookhavenLab/.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Justin Eure

(631) 344-2347

or

Peter Genzer

(631) 344-3174

Copyright © Brookhaven National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Physics

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Superconductivity

![]() Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

![]() 'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

Laboratories

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

![]() NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Tools

![]() Ferroelectrically modulate the Fermi level of graphene oxide to enhance SERS response November 3rd, 2023

Ferroelectrically modulate the Fermi level of graphene oxide to enhance SERS response November 3rd, 2023

![]() The USTC realizes In situ electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy using single nanodiamond sensors November 3rd, 2023

The USTC realizes In situ electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy using single nanodiamond sensors November 3rd, 2023

Energy

![]() Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

Development of zinc oxide nanopagoda array photoelectrode: photoelectrochemical water-splitting hydrogen production January 12th, 2024

![]() Shedding light on unique conduction mechanisms in a new type of perovskite oxide November 17th, 2023

Shedding light on unique conduction mechanisms in a new type of perovskite oxide November 17th, 2023

![]() Inverted perovskite solar cell breaks 25% efficiency record: Researchers improve cell efficiency using a combination of molecules to address different November 17th, 2023

Inverted perovskite solar cell breaks 25% efficiency record: Researchers improve cell efficiency using a combination of molecules to address different November 17th, 2023

![]() The efficient perovskite cells with a structured anti-reflective layer – another step towards commercialization on a wider scale October 6th, 2023

The efficient perovskite cells with a structured anti-reflective layer – another step towards commercialization on a wider scale October 6th, 2023

Photonics/Optics/Lasers

![]() With VECSELs towards the quantum internet Fraunhofer: IAF achieves record output power with VECSEL for quantum frequency converters April 5th, 2024

With VECSELs towards the quantum internet Fraunhofer: IAF achieves record output power with VECSEL for quantum frequency converters April 5th, 2024

![]() Nanoscale CL thermometry with lanthanide-doped heavy-metal oxide in TEM March 8th, 2024

Nanoscale CL thermometry with lanthanide-doped heavy-metal oxide in TEM March 8th, 2024

![]() Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

![]() HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

Research partnerships

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

![]() 'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||