Home > Press > A virus reveals the physics of nanopores

|

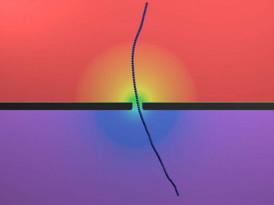

| A better way to study what actually happens at the nanopore A computer simulation depicts an fd virus translocating through a nanopore. Unlike DNA, which tangles up in solution, the fd remains stiff and straight, allowing researchers to study the physics of translocation through nanopores. Credit: Hendrick de Haan/Stein lab/Brown University |

Abstract:

Nanopores could provide a new way to sequence DNA quickly, but the physics involved isn't well understood. That's partly because of the complexities involved in studying the random, squiggly form DNA takes in solution. Researchers from Brown have simplified matters by using a stiff, rod-like virus instead of DNA to experiment with nanopores. Their research has uncovered previously unknown dynamics in polymer-nanopore interactions.

A virus reveals the physics of nanopores

Providence, RI | Posted on June 16th, 2014Nanopores may one day lead a revolution in DNA sequencing. By sliding DNA molecules one at a time through tiny holes in a thin membrane, it may be possible to decode long stretches of DNA at lightning speeds. Scientists, however, haven't quite figured out the physics of how polymer strands like DNA interact with nanopores. Now, with the help of a particular type of virus, researchers from Brown University have shed new light on this nanoscale physics.

"What got us interested in this was that everybody in the field studied DNA and developed models for how they interact with nanopores," said Derek Stein, associate professor of physics and engineering at Brown who directed the research. "But even the most basic things you would hope models would predict starting from the basic properties of DNA — you couldn't do it. The only way to break out of that rut was to study something different."

The findings, published today in Nature Communications, might not only help in the development of nanopore devices for DNA sequencing, they could also lead to a new way of detecting dangerous pathogens.

Straightening out the physics

The concept behind nanopore sequencing is fairly simple. A hole just a few billionths of a meter wide is poked in a membrane separating two pools of salty water. An electric current is applied to the system, which occasionally snares a charged DNA strand and whips it through the pore — a phenomenon called translocation. When a molecule translocates, it causes detectable variations in the electric current across the pore. By looking carefully at those variations in current, scientists may be able to distinguish individual nucleotides — the A's, C's, G's and T's coded in DNA molecules.

The first commercially available nanopore sequencers may only be a few years away, but despite advances in the field, surprisingly little is known about the basic physics involved when polymers interact with nanopores. That's partly because of the complexities involved in studying DNA. In solution, DNA molecules form balls of random squiggles, which make understanding their physical behavior extremely difficult.

For example, the factors governing the speed of DNA translocation aren't well understood. Sometimes molecules zip through a pore quickly; other times they slither more slowly, and nobody completely understands why.

One possible explanation is that the squiggly configuration of DNA causes each molecule to experience differences in drag as they're pulled through the water toward the pore. "If a molecule is crumpled up next to the pore, it has a shorter distance to travel and experiences less drag," said Angus McMullen, a physics graduate student at Brown and the study's lead author. "But if it's stretched out then it would feel drag along the whole length and that would cause it to go slower."

The drag effect is impossible to isolate experimentally using DNA, but the virus McMullen and his colleagues studied offered a solution.

The researchers looked at fd, a harmless virus that infects e. coli bacteria. Two things make the virus an ideal candidate for study with nanpores. First, fd viruses are all identical clones of each other. Second, unlike squiggly DNA, fd virus is a stiff, rod-like molecule. Because the virus doesn't curl up like DNA does, the effect of drag on each one should be essentially the same every time.

With drag eliminated as a source of variation in translocation speed, the researchers expected that the only source of variation would be the effect of thermal motion. The tiny virus molecules constantly bump up against the water molecules in which they are immersed. A few random thermal kicks from the rear would speed the virus up as it goes through the pore. A few kicks from the front would slow it down.

The experiments showed that while thermal motion explained much of the variation in translocation speed, it didn't explain it all. Much to the researchers' surprise, they found another source of variation that increased when the voltage across the pore was increased.

"We thought that the physics would be crystal clear," said Jay Tang, associate professor of physics and engineering at Brown and one of the study's co-authors. "You have this stiff [virus] with well-defined diameter and size and you would expect a very clear-cut signal. As it turns out, we found some puzzling physics we can only partially explain ourselves."

The researchers can't say for sure what's causing the variation they observed, but they have a few ideas.

"It's been predicted that depending on where [an object] is inside the pore, it might be pulled harder or weaker," McMullen said. "If it's in the center of the pore, it pulls a little bit weaker than if it's right on the edge. That's been predicted, but never experimentally verified. This could be evidence of that happening, but we're still doing follow up work."

Toward a nanopore sequencer and more

A better understanding of translocation speed could improve the accuracy of nanopore sequencing, McMullen says. It would also be helpful in the crucial task of measuring the length of DNA strands. "If you can predict the translocation speed," McMullen said, "then you can easily get the length of the DNA from how long its translocation was."

The research also helped to reveal other aspects of the translocation process that could be useful in designing future devices. The study showed that the electrical current tends to align the viruses head first to the pore, but on occasions when they're not lined up, they tend to bounce around on the edge of the pore until thermal motion aligns them to go through. However, when the voltage was turned too high, the thermal effects were suppressed and the virus became stuck to the membrane. That suggests a sweet spot in voltage where headfirst translocation is most likely.

None of this is observable directly — the system is simply too small to be seen in action. But the researchers could infer what was happening by looking at slight changes in the current across the pore.

"When the viruses miss, they rattle around and we see these little bumps in the current," Stein said. "So with these little bumps, we're starting to get an idea of what the molecule is doing before it slides through. Normally these sensors are blind to anything that's going on until the molecule slides through."

That would have been impossible to observe using DNA. The floppiness of the DNA molecule allows it to go through a pore in a folded configuration even if it's not aligned head-on. But because the virus is stiff, it can't fold to go through. That enabled the researchers to isolate and observe those contact dynamics.

"These viruses are unique," Stein said. "They're like perfect little yardsticks."

In addition to shedding light on basic physics, the work might also have another application. While the fd virus itself is harmless, the bacteria it infects — e. coli — is not. Based on this work, it might be possible to build a nanopore device for detecting the presence of fd, and by proxy, e. coli. Other dangerous viruses — Ebola and Marburg among them — share the same rod-like structure as fd.

"This might be an easy way to detect these viruses," Tang said. "So that's another potential application for this."

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grants CBET0846505 and PHYS1058375), and the Brown University Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation. Hendrick W. de Haan, of University of Ontario Institute of Technology, was also an author on the study.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Kevin Stacey

401-863-3766

Copyright © Brown University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Physics

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Nanomedicine

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Grants/Sponsored Research/Awards/Scholarships/Gifts/Contests/Honors/Records

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Research partnerships

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

![]() 'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||