Home > Press > Honeycombs of magnets could lead to new type of computer processing: Imperial scientists take an important step in developing a material using nano-sized magnets that could lead to new electronic devices

|

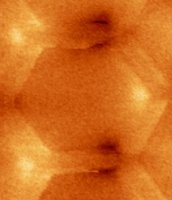

| Honeycomb shaped nano-magnet mesh |

Abstract:

Scientists have taken an important step forward in developing a new material using nano-sized magnets that could ultimately lead to new types of electronic devices, with greater processing capacity than is currently feasible, in a study published today in the journal Science.

Honeycombs of magnets could lead to new type of computer processing: Imperial scientists take an important step in developing a material using nano-sized magnets that could lead to new electronic devices

London, UK | Posted on March 31st, 2012Many modern data storage devices, like hard disk drives, rely on the ability to manipulate the properties of tiny individual magnetic sections, but their overall design is limited by the way these magnetic 'domains' interact when they are close together.

Now, researchers from Imperial College London have demonstrated that a honeycomb pattern of nano-sized magnets, in a material known as spin ice, introduces competition between neighbouring magnets, and reduces the problems caused by these interactions by two-thirds. They have shown that large arrays of these nano-magnets can be used to store computable information. The arrays can then be read by measuring their electrical resistance.

The scientists have so far been able to 'read' and 'write' patterns in the magnetic fields, and a key challenge now is to develop a way to utilise these patterns to perform calculations, and to do so at room temperature. At the moment, they are working with the magnets at temperatures below minus 223°C.

Research author Dr Will Branford and his team have been investigating how to manipulate the magnetic state of nano-structured spin ices using a magnetic field and how to read their state by measuring their electrical resistance. They found that at low temperatures (below minus 223oC) the magnetic bits act in a collective manner and arrange themselves into patterns. This changes their resistance to an electrical current so that if one is passed through the material, this produces a characteristic measurement that the scientists can identify.

The scientists have so far been able to 'read' and 'write' patterns at room temperature. However, at the moment the collective behaviour is only seen at temperatures below minus 223oC. A key challenge now is to develop a way to utilise these patterns to perform calculations, and to do so at room temperature.

Current technology uses one magnetic domain to store a single bit of information. The new finding suggests that a cluster of many domains could be used to solve a complex computational problem in a single calculation. Computation of this type is known as a neural network, and is more similar to how our brains work than to the way in which traditional computers process information.

Dr Branford, who is an EPSRC Career Acceleration Fellow in the Department of Physics at Imperial College London, said: "Electronics manufacturers are trying all the time to squeeze more data into the same devices, or the same data into a tinier space for handheld devices like smart phones and mobile computers. However, the innate interaction between magnets has so far limited what they can do. In some new types of memory, manufacturers try to avoid the limitations of magnetism by avoiding using magnets altogether, using things like ferroelectric (flash) memory, memristors or antiferromagnets instead. However, these solutions are slow, expensive or hard to read out. Our philosophy is to harness the magnetic interactions, making them work in our favour."

Although today's research represents a key step forward, the researchers say there are many hurdles to overcome before scientists will be able to create prototype devices based on this technique such as developing an algorithm to control the computation. The nature of this algorithm will determine whether the room temperature state can be used or if the low temperature collective behaviour is required. However, they are optimistic that if these challenges can be tackled successfully, new technology using magnetic honeycombs might be available in ten to fifteen years.

In experiments, Dr Branford applied an electrical current across a continuous honeycomb mesh, made from cobalt magnetic bars each 1 micrometer long and 100 nanometres wide, and covering an area 100 square micrometers (as pictured). A single unit of the honeycomb mesh is like three bar magnets meeting in the centre of a triangle. There is no way to arrange them without having either two north poles or two south poles touching and repelling each other, this is called a 'frustrated' magnetic system. In a single triangular unit there are six ways to arrange the magnets such that they have exactly the same level of frustration, and as you increase the number of triangular units in the honeycomb, the number of possible arrangements of magnets increases exponentially, increasing the complexity of possible patterns.

Previous studies have shown that external magnetic fields can cause the magnetic domain of each bar to change state. This in turn affects the interaction between that bar and its two neighbouring bars in the honeycomb, and it is this pattern of magnetic states that Dr Branford says could be computer data.

Dr Branford said: "The strong interaction between neighbouring magnets allows us to subtly affect how the patterns form across the honeycomb. This is something we can take advantage of to compute complex problems because many different outcomes are possible, and we can differentiate between them electronically. Our next big challenge is to make an array of nano-magnets that can be 'programmed' without using external magnetic fields."

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Simon Levey

44-020-759-46702

Copyright © Imperial College London

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

Physics

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Chip Technology

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

![]() HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

Memory Technology

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

![]() Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

Interdisciplinary: Rice team tackles the future of semiconductors Multiferroics could be the key to ultralow-energy computing October 6th, 2023

![]() Researchers discover materials exhibiting huge magnetoresistance June 9th, 2023

Researchers discover materials exhibiting huge magnetoresistance June 9th, 2023

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||