Home > Press > Batteries Made From World’s Thinnest Material Could Power Tomorrow’s Electric Cars: Engineering Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Use Intentionally Blemished Graphene Paper To Create Easy-To-Make, Quick-Charging Lithium-ion Battery With High Power Density

|

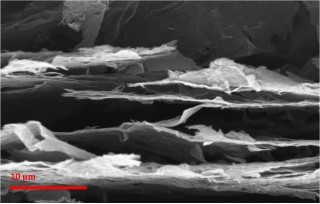

| Engineering researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute made a sheet of paper from the world’s thinnest material, graphene, and then zapped the paper with a laser or camera flash to blemish it with countless cracks, pores, and other imperfections. The result is a graphene anode material that can be charged or discharged 10 times faster than conventional graphite anodes used in lithium (Li)-ion batteries for today’s mobile phones, laptop and tablet computers, and even electric automobiles. The intentional imperfections, as seen in this scanning electron micrograph, are critical for the device’s ability to quickly accept or discharge large amounts of energy. |

Abstract:

Engineering researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute made a sheet of paper from the world's thinnest material, graphene, and then zapped the paper with a laser or camera flash to blemish it with countless cracks, pores, and other imperfections. The result is a graphene anode material that can be charged or discharged 10 times faster than conventional graphite anodes used in today's lithium (Li)-ion batteries.

Batteries Made From World’s Thinnest Material Could Power Tomorrow’s Electric Cars: Engineering Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Use Intentionally Blemished Graphene Paper To Create Easy-To-Make, Quick-Charging Lithium-ion Battery With High Power Density

Troy, NY | Posted on August 22nd, 2012Rechargeable Li-ion batteries are the industry standard for mobile phones, laptop and tablet computers, electric cars, and a range of other devices. While Li-ion batteries have a high energy density and can store large amounts of energy, they suffer from a low power density and are unable to quickly accept or discharge energy. This low power density is why it takes about an hour to charge your mobile phone or laptop battery, and why electric automobile engines cannot rely on batteries alone and require a supercapacitor for high-power functions such as acceleration and braking.

The Rensselaer research team, led by nanomaterials expert Nikhil Koratkar, sought to solve this problem and create a new battery that could hold large amounts of energy but also quickly accept and release this energy. Such an innovation could alleviate the need for the complex pairing of Li-ion batteries and supercapacitors in electric cars, and lead to simpler, better-performing automotive engines based solely on high-energy, high-power Li-ion batteries. Koratkar and his team are confident their new battery, created by intentionally engineering defects in graphene, is a critical stepping stone on the path to realizing this grand goal. Such batteries could also significantly shorten the time it takes to charge portable electronic devices from phones and laptops to medical devices used by paramedics and first responders.

"Li-ion battery technology is magnificent, but truly hampered by its limited power density and its inability to quickly accept or discharge large amounts of energy. By using our defect-engineered graphene paper in the battery architecture, I think we can help overcome this limitation," said Koratkar, the John A. Clark and Edward T. Crossan Professor of Engineering at Rensselaer. "We believe this discovery is ripe for commercialization, and can make a significant impact on the development of new batteries and electrical systems for electric automobiles and portable electronics applications."

Results of the study were published this week by the journal ACS Nano in the paper "Photo-thermally reduced graphene as high power anodes for lithium ion batteries." See the paper online at: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/nn303145j

Koratkar and his team started investigating graphene as a possible replacement for the graphite used as the anode material in today's Li-ion batteries. Essentially a single layer of the graphite found commonly in our pencils or the charcoal we burn on our barbeques, graphene is an atom-thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged like a nanoscale chicken-wire fence. In previous studies, Li-ion batteries with graphite anodes exhibited good energy density but low power density, meaning they could not charge or discharge quickly. This slow charging and discharging was because lithium ions could only physically enter or exit the battery's graphite anode from the edges, and slowly work their way across the length of the individual layers of graphene.

Koratkar's solution was to use a known technique to create a large sheet of graphene oxide paper. This paper is about the thickness of a piece of everyday printer paper, and can be made nearly any size or shape. The research team then exposed some of the graphene oxide paper to a laser, and other samples of the paper were exposed to a simple flash from a digital camera. In both instances, the heat from the laser or photoflash literally caused mini-explosions throughout the paper, as the oxygen atoms in graphene oxide were violently expelled from the structure. The aftermath of this oxygen exodus was sheets of graphene pockmarked with countless cracks, pores, voids, and other blemishes. The pressure created by the escaping oxygen also prompted the graphene paper to expand five-fold in thickness, creating large voids between the individual graphene sheets.

The researchers quickly learned this damaged graphene paper performed remarkably well as an anode for a Li-ion battery. Whereas before the lithium ions slowly traversed the full length of graphene sheets to charge or discharge, the ions now used the cracks and pores as shortcuts to move quickly into or out of the graphene—greatly increasing the battery's overall power density. Koratkar's team demonstrated how their experimental anode material could charge or discharge 10 times faster than conventional anodes in Li-ion batteries without incurring a significant loss in its energy density. Despite the countless microscale pores, cracks, and voids that are ubiquitous throughout the structure, the graphene paper anode is remarkably robust, and continued to perform successfully even after more than 1,000 charge/discharge cycles. The high electrical conductivity of the graphene sheets also enabled efficient electron transport in the anode, which is another necessary property for high-power applications.

Koratkar said the process of making these new graphene paper anodes for Li-ion batteries can easily be scaled up to suit the needs of industry. The graphene paper can be made in essentially any size and shape, and the photo-thermal exposure by laser or camera flashes is an easy and inexpensive process to replicate. The researchers have filed for patent protection for their discovery. The next step for this research project is to pair the graphene anode material with a high-power cathode material to construct a full battery.

Along with Koratkar, co-authors of the paper are Rensselaer graduate students Rahul Mukherjee, Abhay Varghese Thomas, and Ajay Krishnamurthy, all of the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Nuclear Engineering (MANE).

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, and supported by Koratkar's John A. Clark and Edward T.Crossan Endowed Chair Professorship at Rensselaer.

Koratkar is a professor in MANE and the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Rensselaer. He is also a faculty member of the university's Center for Future Energy Systems and the Rensselaer Nanotechnology Center.

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Michael Mullaney

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Troy, NY

518-276-6161

www.rpi.edu/news

Copyright © Newswise

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

![]() Nature Materials Study: Graphene “Invisible” to Water

Nature Materials Study: Graphene “Invisible” to Water

![]() Graphene Foam Detects Explosives, Emissions Better Than Today’s Gas Sensors

Graphene Foam Detects Explosives, Emissions Better Than Today’s Gas Sensors

![]() New Graphene Discovery Boosts Oil Exploration Efforts, Could Enable Self-Powered Microsensors

New Graphene Discovery Boosts Oil Exploration Efforts, Could Enable Self-Powered Microsensors

![]() Water Could Hold Answer to Graphene Nanoelectronics

Water Could Hold Answer to Graphene Nanoelectronics

![]() Graphene Outperforms Carbon Nanotubes for Creating Stronger Materials

Graphene Outperforms Carbon Nanotubes for Creating Stronger Materials

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Graphene/ Graphite

![]() NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Automotive/Transportation

![]() Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

Researchers’ approach may protect quantum computers from attacks March 8th, 2024

![]() Tests find no free-standing nanotubes released from tire tread wear September 8th, 2023

Tests find no free-standing nanotubes released from tire tread wear September 8th, 2023

Battery Technology/Capacitors/Generators/Piezoelectrics/Thermoelectrics/Energy storage

![]() What heat can tell us about battery chemistry: using the Peltier effect to study lithium-ion cells March 8th, 2024

What heat can tell us about battery chemistry: using the Peltier effect to study lithium-ion cells March 8th, 2024

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||