Home > Press > Plants exhibit a wide range of mechanical properties, engineers find Biological structures may help engineers design new materials

|

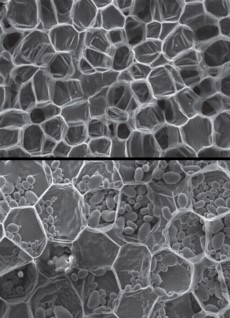

| A scanning electron micrograph of carrot, top, and potato, bottom, showing relatively thin-walled cells. The oval objects within the potato tissue are starch granules. Images: Don Galler |

Abstract:

From an engineer's perspective, plants such as palm trees, bamboo, maples and even potatoes are examples of precise engineering on a microscopic scale. Like wooden beams reinforcing a house, cell walls make up the structural supports of all plants. Depending on how the cell walls are arranged, and what they are made of, a plant can be as flimsy as a reed, or as sturdy as an oak.

Plants exhibit a wide range of mechanical properties, engineers find Biological structures may help engineers design new materials

Cambridge, MA | Posted on August 14th, 2012An MIT researcher has compiled data on the microstructures of a number of different plants, from apples and potatoes to willow and spruce trees, and has found that plants exhibit an enormous range of mechanical properties, depending on the arrangement of a cell wall's four main building blocks: cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin and pectin.

Lorna Gibson, the Matoula S. Salapatas Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at MIT, says understanding plants' microscopic organization may help engineers design new, bio-inspired materials.

"If you look at engineering materials, we have lots of different types, thousands of materials that have more or less the same range of properties as plants," Gibson says. "But here the plants are, doing it arranging just four basic constituents. So maybe there's something you can learn about the design of engineered materials."

A paper detailing Gibson's findings has been published this month in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

To Gibson, a cell wall's components bear a close resemblance to certain manmade materials. For example, cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin can be as stiff and strong as manufactured polymers. A plant's cellular arrangement can also have engineering parallels: cells in woods, for instance, are aligned, similar to engineering honeycombs, while polyhedral cell configurations, such as those found in apples, resemble some industrial foams.

To explore plants' natural mechanics, Gibson focused on three main plant materials: woods, such as cedar and oak; parenchyma cells, which are found in fruits and root vegetables; and arborescent palm stems, such as coconut trees. She compiled data from her own and other groups' experiments and analyzed two main mechanical properties in each plant: stiffness and strength.

Among all plants, Gibson observed wide variety in both properties. Fruits and vegetables such as apples and potatoes were the least stiff, while the densest palms were 100,000 times stiffer. Likewise, apples and potatoes fell on the lower end of the strength scale, while palms were 1,000 times stronger.

"There are plants with properties over that whole range," Gibson says. "So it's not like potatoes are down here, and wood is over there, and there's nothing in between. There are plants with properties spanning that whole huge range. And it's interesting how the plants do that."

It turns out the large range in stiffness and strength stems from an intricate combination of plant microstructures: the composition of the cell wall, the number of layers in the cell wall, the arrangement of cellulose fibers in those layers, and how much space the cell wall takes up.

In trees such as maples and oaks, cells grow and multiply in the cambium layer, just below the bark, increasing the diameter of the trees. The cell walls in wood are composed of a primary layer with cellulose fibers randomly spread throughout it. Three secondary layers lie underneath, each with varying compositions of lignin and cellulose that wind helically through each layer.

Taken together, the cell walls occupy a large portion of a cell, providing structural support. The cells in woods are organized in a honeycomb pattern — a geometric arrangement that gives wood its stiffness and strength.

Parenchyma cells, found in fruits and root vegetables, are much less stiff and strong than wood. The cell walls of apples, potatoes and carrots are much thinner than in wood cells, and made up of only one layer. Cellulose fibers run randomly throughout this layer, reinforcing a matrix of hemicellulose and pectin. Parenchyma cells have no lignin; combined with their thin walls and the random arrangement of their cellulose fibers, Gibson says, this may explain their cell walls' low stiffness. The cells in each plant are densely packed together, similar to industrial foams used in mattresses and packaging.

Unlike woody trees that grow in diameter over time, the stems of arborescent palms such as coconut trees maintain similar diameters throughout their lifetimes. Instead, as the stem grows taller, palms support this extra weight by increasing the thickness of their cell walls. A cell wall's thickness depends on where it is along a given palm stem: Cell walls are thicker at the base and periphery of stems, where bending stresses are greatest.

Gibson sees plant mechanics as a valuable resource for engineers designing new materials. For instance, she says, researchers have developed a wide array of materials, from soft elastomers to stiff, strong alloys. Carbon nanotubes have been used to reinforce composite materials, and engineers have made honeycomb-patterned materials with cells as small as a few millimeters wide. But researchers have been unable to fabricate cellular composite materials with the level of control that plants have perfected.

"Plants are multifunctional," Gibson says. "They have to satisfy a number of requirements: mechanical ones, but also growth, surface area for sunlight and transport of fluids. The microstructures plants have developed satisfy all these requirements. With the development of nanotechnology, I think there is potential to develop multifunctional engineering materials inspired by plant microstructures."

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

####

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Sarah McDonnell

MIT News Office

T: 617-253-8923

Copyright © MIT

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Nanotubes/Buckyballs/Fullerenes/Nanorods/Nanostrings

![]() Tests find no free-standing nanotubes released from tire tread wear September 8th, 2023

Tests find no free-standing nanotubes released from tire tread wear September 8th, 2023

![]() Detection of bacteria and viruses with fluorescent nanotubes July 21st, 2023

Detection of bacteria and viruses with fluorescent nanotubes July 21st, 2023

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Materials/Metamaterials/Magnetoresistance

![]() Nanoscale CL thermometry with lanthanide-doped heavy-metal oxide in TEM March 8th, 2024

Nanoscale CL thermometry with lanthanide-doped heavy-metal oxide in TEM March 8th, 2024

![]() Focused ion beam technology: A single tool for a wide range of applications January 12th, 2024

Focused ion beam technology: A single tool for a wide range of applications January 12th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Nanobiotechnology

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||