Home > Press > UA Physicists Take New Look at the Atom

|

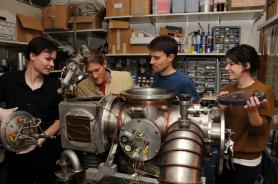

| Graduate student Vincent Lonij (left), associate professor of physics Alex Cronin, research assistant Will Holmgren and undergraduate student Catherine Klauss perform maintenance on a chamber used to beam atoms through a grating to measure a tiny force that helps physicists better understand the structure of atoms. (Photo by Norma Jean Gargasz/UANews) |

Abstract:

UA physicists discovered a new way to measure how single atoms interact with surfaces. Their findings help develop nanotechnology and test new theories about the internal structure of atoms.

By Daniel Stolte, University

UA Physicists Take New Look at the Atom

Tucson, AZ | Posted on January 17th, 2011Measuring the attractive forces between atoms and surfaces with unprecedented precision, University of Arizona physicists have produced data that could refine our understanding of the structure of atoms and improve nanotechnology. The discovery has been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Van der Waals forces are fundamental for chemistry, biology and physics. However, they are among the weakest known chemical interactions, so they are notoriously hard to study. This force is so weak that it is hard to notice in everyday life. But delve into the world of micro-machines and nano-robots, and you will feel the force - everywhere.

"If you make your components small enough, eventually this van-der-Waals potential starts to become the dominant interaction," said Vincent Lonij, a graduate student in the UA department of physics who led the research as part of his doctoral thesis.

"If you make tiny, tiny gears for a nano-robot, for example, those gears just stick together and grind to a halt. We want to better understand how this force works."

To study the van-der-Waals force, Lonij and his co-workers Will Holmgren, Cathy Klauss and associate professor of physics Alex Cronin designed a sophisticated experimental setup that can measure the interactions between single atoms and a surface. The physicists take advantage of quantum mechanics, which states that atoms can be studied and described both as particles and as waves.

"We shoot a beam of atoms through a grating, sort of like a micro-scale picket fence," Lonij explained. "As the atoms pass through the grating, they interact with the surface of the grating bars, and we can measure that interaction."

As the atoms pass through the slits in the grating, the van-der-Waals force attracts them to the bars separating the slits. Depending on how strong the interaction, it changes the atom's trajectory, just like a beam of light is bent when it passes through water or a prism.

A wave passing through the middle of the slit does so relatively unencumbered. On the other hand, if an atom wave passes close by the slit's edges, it interacts with the surface and skips a bit ahead, "out of phase," as physicists say.

"After the atoms pass through the grating, we detect how much the waves are out of phase, which tells us how strong the van-der-Waals potential was when the atoms interacted with the surface."

Mysterious as it seems, without the van-der-Waals force, life would be impossible. For example, it helps the proteins that make up our bodies to fold into the complex structures that enable them to go about their highly specialized jobs.

Unlike magnetic attraction, which affects only metals or matter carrying an electric current, van-der-Waals forces make anything stick to anything, provided the two are extremely close to each other. Because the force is so weak, its action doesn't range beyond the scale of atoms - which is precisely the reason why there is no evidence of such a force in our everyday world and why we leave it to physicists such as Lonij to unravel its secrets.

Initially, he was driven simply by curiosity, Lonij said. When he started his project, he didn't know it would lead to a new way of measuring the forces between atoms and surfaces that may change the way physicists think about atoms.

And with a smile, he added, "I thought it would be fitting to study this force, since I am from the Netherlands; Mr. van der Waals was Dutch, too."

In addition to proving that core electrons contribute to the van-der-Waals potential, Lonij and his group made another important discovery.

Physicists around the world who are studying the structure of the atom are striving for benchmarks that enable them to test their theories about how atoms work and interact. "Our measurements of atom-surface potentials can serve as such benchmarks," Lonij explained. "We can now test atomic theory in a new way."

Studying how atoms interact is difficult because they are not simply tiny balls. Instead, they are what physicists call many-body systems. "An atom consists of a whole bunch of other particles, electrons, neutrons, protons, and so forth," Lonij said.

Even though the atom as a whole holds no net electric charge, the different charged particles moving around in its interior are what create the van-der-Waals force in the first place.

"What happens is that the electrons, which hold all the negative charge, and the protons, which hold all the positive charge, are not always in the same places. So you can have tiny little differences in charge that are fluctuating very fast. If you put a charge close to a surface, you induce an image charge. In a highly simplified way, you could say the atom is attracted to its own reflection."

To physicists, who prefer things neat and clean and tractable with razor-sharp mathematics, such a system, made up from many smaller particles zooming around each other, is difficult to pin down. To add to the complication, most surfaces are not clean. As Lonij puts it, "Comparing such a dirty system to theory is a big challenge, but we figured out a way to do it anyway."

"A big criticism of this type of work always was, ‘well, you're measuring this atom-surface potential, but you don't know what the surface looks like so you don't know what you're really measuring.'"

To eliminate this problem, Lonij's team used different types of atoms and looked at how each interacted with the same surface.

"Our technique gives you the ratio of potentials directly without ever knowing the potential for either of the two atoms," he said. "When I started five years ago, the uncertainty in these types of measurements was 20 percent. We brought it down to two percent."

The most significant discovery was that an atom's inner electrons, orbiting the nucleus at a closer range than the atom's outer electrons, influence the way the atom interacts with the surface.

"We show that these core electrons contribute to the atom-surface potential," Lonij said, "which was only known in theory until now. This is the first experimental demonstration that core electrons affect atom-surface potentials."

"But what is perhaps more important," he added, "is that you can also turn it around. We now know that the core electrons affect atom-surface potentials. We also know that these core electrons are hard to calculate in atomic theory. So we can use measurements of atom-surface potentials to make the theory better: The theory of the atom."

####

For more information, please click here

Copyright © University of Arizona

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Physics

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Academic/Education

![]() Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

Rice University launches Rice Synthetic Biology Institute to improve lives January 12th, 2024

![]() Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Multi-institution, $4.6 million NSF grant to fund nanotechnology training September 9th, 2022

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Tools

![]() Ferroelectrically modulate the Fermi level of graphene oxide to enhance SERS response November 3rd, 2023

Ferroelectrically modulate the Fermi level of graphene oxide to enhance SERS response November 3rd, 2023

![]() The USTC realizes In situ electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy using single nanodiamond sensors November 3rd, 2023

The USTC realizes In situ electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy using single nanodiamond sensors November 3rd, 2023

Quantum nanoscience

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

Optically trapped quantum droplets of light can bind together to form macroscopic complexes March 8th, 2024

![]() Bridging light and electrons January 12th, 2024

Bridging light and electrons January 12th, 2024

![]() 'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

'Sudden death' of quantum fluctuations defies current theories of superconductivity: Study challenges the conventional wisdom of superconducting quantum transitions January 12th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||