Home > Press > Nanoscopic particles resist full encapsulation, Sandia simulations show

|

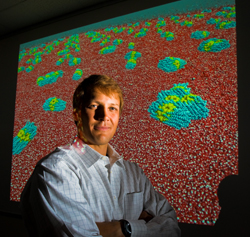

| Sandia researcher Matt Lane stands before computer simulations of 2-nm. gold particles too small to measure experimentally. The particles aggregate to produce cigar-shaped objects that prefer to sit at the water’s surface. Red represents oxygen, blue carbon, white hydrogen, yellow the sulfur coating. The gold particles are not modeled directly. (Photo by Randy Montoya) |

Abstract:

Formerly unrealized defect results in clumping and unwanted chemical interactions

Nanoscopic particles resist full encapsulation, Sandia simulations show

Albuquerque, NM | Posted on October 11th, 2010It may seem obvious that dunking relatively spherical objects in a sauce — blueberries in melted chocolate, say — will result in an array of completely encapsulated berries.

Relying on that concept, fabricators of spherical nanoparticles have similarly dunked their wares in protective coatings in the belief such encapsulations would prevent clumping and unwanted chemical interactions with solvents.

Unfortunately, reactions in the nanoworld are not logical extensions of the macroworld, Sandia National Laboratories researchers Matthew Lane and Gary Grest have found.

In a cover article this past summer in Physical Review Letters, the researchers use molecular dynamics simulations to show that simple coatings are incapable of fully covering each spherical nanoparticle in a set.

Instead, because the diameter of a particle may be smaller than the thickness of the coating protecting it, the curvature of the particle surface as it rapidly drops away from its attached coating provokes the formation of a series of louvres rather than a solid protective wall (see illustration).

"We've known for some time now that nanoparticles are special, and that ‘small is different,'" Lane said. "What we've shown is that this general rule for nanotechnology applies to how we coat particles, too."

Carlos Gutierrez, manager of Sandia's Surfaces and Interface Sciences Department, said, "It's well-known that aggregation of nanoparticles in suspension is presently an obstacle to their commercial and industrial use. The simulations show that even coatings fully and uniformly applied to spherical nanoparticles are significantly distorted at the water-vapor interface."

Said Grest, "You don't want aggregation because you want the particles to stay distributed throughout the product to achieve uniformity. If you have particles of, say, micron-size, you have to coat or electrically charge them so the particles don't stick together. But when particles get small and the coatings become comparable in size to the particles, the shapes they form are asymmetric rather than spherical. Spherical particles keep their distance; asymmetric particles may stick to each other."

The simulation's finding isn't necessarily a bad thing, for this reason: Though each particle is coated asymmetrically, the asymmetry is consistent for any given set. Said another way, all coated nanoscopic sets are asymmetric in their own way.

A predictable, identical variation occurring in every member of a nanoset could open doors to new applications.

"What we've done here is to put up a large ‘dead end' sign to prevent researchers from wasting time going down the wrong path," Lane said. "Increasing surface density of the coating or its molecular chain length isn't going to improve patchy coatings, as it would for larger particles. But there are numerous other possible paths to new outcomes when you can control the shape of the aggregation."

The paper, "Spontaneous Asymmetry of Coated Spherical Nanoparticles in Solution and at Liquid-Vapor Interfaces," was published on June 9 in Physical Review Letters 104, 235501 (2010).

The computations were carried out at the New Mexico Computing Application Center. The work was supported, in part, by the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, a U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences user facility and by the National Institute for NanoEngineering through Laboratory Directed Research and Development program at Sandia National Laboratories.

####

About Sandia National Laboratories

Sandia National Laboratories is a multiprogram laboratory operated and managed by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corporation, for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration. With main facilities in Albuquerque, N.M., and Livermore, Calif., Sandia has major R&D responsibilities in national security, energy and environmental technologies, and economic competitiveness.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Neal Singer

(505) 845-7078

Copyright © Sandia National Laboratories

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||