Home > Press > How Do Bacteria Swim? Brown Physicists Explain

|

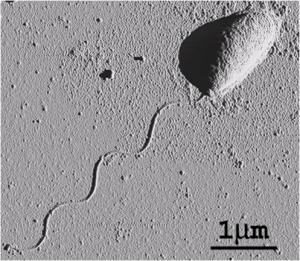

| Bacterial Locomotion Brown physicists have completed the most detailed study of how bacteria such as the single-celled Caulobacter crescentus swim and how that swimming motion is influenced by drag and a phenomenon known as Brownian motion. Credit: Guanglai Li/Brown University |

Abstract:

Brown University physicists have completed the most detailed study of the swimming patterns of a microbe, showing for the first time how its movement is affected by drag and a phenomenon called Brownian motion. The findings appear online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

How Do Bacteria Swim? Brown Physicists Explain

Providence, RI | Posted on November 19th, 2008Imagine yourself swimming in a pool: It's the movement of your arms and legs, not the viscosity of the water, that mostly dictates the speed and direction that you swim.

For tiny organisms, the situation is different. Microbes' speed and direction are subjected more to the physical vagaries of the fluid around them.

"For bacteria to swim in water," explained Jay Tang, associate professor of physics at Brown University, "it's like us trying to swim through honey. The drag is dominant."

Tang and his team at Brown have just completed the most detailed study of the swimming patterns of one particular bacterium, Caulobacter crescentus. In a paper published online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in print Nov. 25), the researchers show how this microbe's movement is affected by drag and a phenomenon called Brownian motion. The observations would appear to hold true for many other bacteria, Tang said, and shed light on how these organisms scavenge for food and how they approach surfaces and "stick" to them.

Caulobacter is a single-celled organism with a filament-like tail called a flagellum. As it swims, its rounded cellular head rotates in one direction, while the tail rotates in the opposite direction. This creates torque, which helps explain the bacterium's nonlinear movement through a fluid. What Tang and his team found, however, is that Caulobacter also is influenced by Brownian motion, which is the zigzagging motion that occurs when immersed particles are buffeted by the actions of the molecules of the surrounding medium. What that means, in effect, is that Caulobacter is being pinballed by the water molecules surrounding it as it swims.

This twin effect of hydrodynamic interaction and Brownian motion governs the circular swimming patterns of Caulobacter and many other microorganisms, the scientists found.

"Random forces are always more important the smaller the object is," said Tang, whose team included Guanglai Li, assistant professor of physics (research) at Brown, and Lick-Kong Tam, a recent Brown graduate who is now studying biomedical engineering at Yale University. "At Caulobacter's size, the random forces become dominant."

The researchers also discovered another clue to the swimming behavior: Caulobacter's swimming circles grew tighter as the bacterium got closer to a surface boundary, in this case a glass slide. The tighter circle, the team found, is the result of more drag being exerted on the microbe as it swims closer to the surface. When the microbe was farther away from the surface, it encountered less drag, and its swimming circle was wider, the group learned.

It's this zigzagging effect that helps explain why "most of the time, these cells are not as close to the surface as they are predicted to be," Tang said. "The reason is Brownian motion, because they are jumping around."

That finding is important, because it helps explain the feedings areas for simple-celled organisms. Perhaps more importantly, it may help scientists understand how bacteria ultimately arrive at a surface and adhere to it. The applications range from better understanding the flow and adhesion of platelets in the bloodstream to greater insights into how contaminants are captured as they percolate through the soil.

"As it turns out, swimming is an important mechanism to that adhesion process," Tang said.

The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation funded the work.

####

For more information, please click here

Copyright © Brown University

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

Physics

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Govt.-Legislation/Regulation/Funding/Policy

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||