Home > Press > Surprising Graphene: Honing in on graphene electronics with infrared synchrotron radiation

|

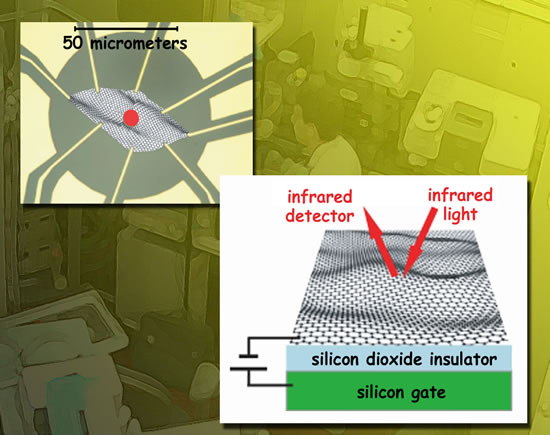

| A flake of exfoliated graphene 50 micrometers square was placed on layers of silicon dioxide insulator and a silicon gate. The schematic, left, shows how gold contacts were attached to the graphene to apply gate voltage. A 10-micrometer beam of infrared synchrotron radiation (red spot) was focused onto the graphene to measure transmission and reflectance spectra. |

Abstract:

Graphene is the two-dimensional crystalline form of carbon: a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in hexagons, like a sheet of chicken wire with an atom at each nexus. As free-standing objects, such two-dimensional crystals were believed impossible to create — even to exist — until physicists at the University of Manchester actually made graphene in 2004.

Surprising Graphene: Honing in on graphene electronics with infrared synchrotron radiation

BERKELEY, CA | Posted on June 10th, 2008Now researchers at the Department of Energy's Advanced Light Source (ALS), from DOE's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), have measured the extraordinary properties of graphene with an accuracy never before achieved.

The results confirm many of the strangest features of the unusual material but also reveal significant departures from theoretical predictions. And they point the way to novel practical applications, such as tunable optical modulators for communications and other nanoscale electronics.

The studies were performed by Zhiqiang Li, an ALS Doctoral Fellow from Dimitri Basov's laboratory at UCSD, working with colleagues at Columbia University in New York and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Florida, and with Berkeley Lab's Michael Martin, who manages the Fourier Transform Infrared beamline 1.4.4 at the ALS. The researchers report their findings in the June issue of the journal Nature Physics.

Graphene's promising electronic properties

The familiar pencil-lead form of carbon, graphite, consists of layers of carbon atoms tightly bonded in the plane but only loosely bonded between planes; because the layers move easily over one another, graphite is a good lubricant. In fact these graphite layers are graphene, although they had never been observed in isolation before 2004. Once demonstrated, research immediately took off, inspired by the material's unexpected electronic properties. Experiments continue unabated.

"Graphene's unusual electronic properties arise from the fact that the carbon atom has four electrons, three of which are tied up in bonding with its neighbors," says Li. "But the unbound fourth electrons are in orbitals extending vertically above and below the plane, and the hybridization of these spreads across the whole graphene sheet."

As a crystal, two-dimensional graphene is quite dissimilar from three-dimensional materials such as silicon. In semiconductors and other materials, charge carriers (electrons and oppositely charged "holes") interact with the periodic field of the atomic lattice to form quasiparticles (excitations that act like actual particles). But quasiparticles in graphene do not look anything like an ordinary semiconductor's.

The energy of quasiparticles in a solid depends on their momentum, a relationship described by energy bands. In a typical 3-D semiconductor, the energy bands are "parabolic" — a graph of the lower, filled valence band resembles a stalagmite, more or less flat on top, while the upper, empty conduction band is its opposite, a stalactite, more or less flat on the bottom; between them is the open band gap, representing the amount of energy it takes to boost an electron from the valence band to the conduction band.

Unlike in ordinary semiconductors, however, graphs of the valence band and the conduction band in graphene are smooth-sided cones that meet at a point, called the Dirac point. These plot the energy-momentum relationships of quasiparticles behaving as if they were massless electrons, so-called Dirac fermions, which travel at a constant speed — a small but noteworthy fraction of the speed of light.

One interesting consequence of this unique band structure is that the electrons in graphene are "sort of free," Li says. Unlike electrons in other materials, the electrons in graphene move ballistically — without collisions — over great distances, even at room temperature. As a result, the ability of the electrons in graphene to conduct electrical current is 10 to 100 times greater than those in a normal semiconductor like silicon at room temperature. This makes graphene a very promising candidate for future electronic applications.

Says Li, "By applying a gate voltage to graphene which has been integrated in a gated device, one can continually control the carrier density by varying the voltage, and thus the conductivity." It's this phenomenon that gives rise to graphene's practical promise.

An unusual experiment

Because graphene is tricky to make and even trickier to handle, most experiments have been performed not on free-standing monolayers but on two types of graphene samples: exfoliated graphene, deposited on a silicon-oxide/silicon substrate, and epitaxial graphene, a layer of carbon atoms chemically deposited (and chemically bonded to) a substrate of silicon carbide.

"Epitaxial graphene and exfoliated graphene are very distinct," says Li. Much of the synchrotron experimental work on epitaxial graphene has employed ARPES, angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. "In our work, we investigated exfoliated graphene by employing infrared spectromicroscopy."

Li explains that infrared measurements can probe the dynamical properties of quasiparticles over a wide energy range, and therefore can provide some of the most interesting information about the electronic properties of a material, "such as electron lifetime and interactions between electrons," he says. "Such measurements have not been performed on exfoliated graphene before, because it is extremely difficult to measure the absorption of light in a single monolayer of graphene."

To accurately measure how graphene's infrared absorption responds to varying the gate voltages, the researchers first needed samples of exfoliated graphene attached to electrodes. They used flakes of single-atomic-layer graphene 50 micrometers (millionths of a meter) square. The samples were laid on top of (but not chemically bonded to) an insulating layer of silicon oxide and an underlying layer of pure silicon. This transparent substrate acted as the gate electrode. The whole system was cooled to 45 kelvins (379 degrees Fahrenheit below zero).

"To measure the absorption of infrared light by neutral graphene and by electrostatically doped graphene" — that is, not chemically doped, but rather "doped" by the gate voltage — "we needed the intensity and tight focus of a beam of synchrotron radiation operating at infrared frequencies," says Michael Martin. "The ALS IR beam, less than 10 micrometers across, was positioned at various points across the sample, which allowed us to directly measure transmission and reflectance and obtain the sample's optical conductivity."

The term "optical" in optical conductivity refers to the high frequency of light, as opposed to the very low frequency of household alternating current (ac). The researchers induced optical-frequency ac in the graphene sample with the infrared beam and manipulated the voltage via the electrodes. The changes in voltage changed the conductivity and carrier density in the sample, and directly affected its ability to transmit or reflect light. Indeed, the researchers found that the reflectance and transmission of graphene can be dramatically tuned by applied gate voltages.

"In a normal electronic system such as a semiconductor, the Fermi energy" — the energy of the carriers' highest occupied quantum state when the temperature is absolute zero — "is proportional to the density of the carriers," Li says. "But in a system of 2-D Dirac fermions, the Fermi energy is proportional to the square root of the carrier density."

The researchers observed this unique square-root density dependence of the Fermi energy, which verifies that electrons in graphene indeed behave like Dirac fermions. Thus many of the effects predicted for graphene by theory were confirmed in these experiments, and measured to an accuracy never before obtained.

Graphene surprises

Other results, however, revealed "many-body interactions," more complex than what had been suggested by the "single-particle" picture of graphene, which treats the carriers as an ensemble of independent particles. Theories predict that if electrons in graphene experience no interactions with one another or with the carbon atoms, then at low energy (or frequency) — energy below twice the Fermi energy — they will absorb hardly any light.

Instead, the researchers observed considerable absorption of infrared light in this low-energy region. "This unexpected absorption may stem from interactions between electrons and lattice vibrational modes of the carbon atoms, or from mutual interactions among electrons," says Li.

Another surprise is the speed of the electrons. As independent particles, electrons in graphene should travel at a constant speed regardless of their energy. The researchers found that, at high energies, electrons in graphene indeed move at constant speed — but their speed increases systematically as their energy is lowered. This enigmatic behavior may be due to electron-electron interactions, predicted theoretically in 1994.

"Many-body interactions could be as simple as Coulomb interactions between electrons, or they could be more complicated," says Martin. "The data give a clear signature, but we don't completely understand them."

"Some of these effects might be related to the limitations of the samples we studied," says Li. "We'd like to do the measurements on samples suspended over a void, so as to eliminate any disorder induced by the substrate. Still, even allowing for refinements, it appears that our measurements present a challenge to the current understanding of this intriguing material."

"Dirac charge dynamics in graphene by infrared spectroscopy," by Z. Q. Li, E. A. Henriksen, Z. Jiang, Z. Hao, M. C. Martin, P. Kim, H. L. Stormer, and D. N. Basov, appears in the June issue of Nature Physics and is available online to subscribers at http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/vaop/ncurrent/index.html.

####

About Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Paul Preuss

(510) 486-6249

Copyright © Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related Links |

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Laboratories

![]() A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

A battery’s hopping ions remember where they’ve been: Seen in atomic detail, the seemingly smooth flow of ions through a battery’s electrolyte is surprisingly complicated February 16th, 2024

![]() NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

NRL discovers two-dimensional waveguides February 16th, 2024

![]() Three-pronged approach discerns qualities of quantum spin liquids November 17th, 2023

Three-pronged approach discerns qualities of quantum spin liquids November 17th, 2023

Chip Technology

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

![]() HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

HKUST researchers develop new integration technique for efficient coupling of III-V and silicon February 16th, 2024

Nanomedicine

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

![]() Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Researchers develop artificial building blocks of life March 8th, 2024

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||