Home > Press > Fine print: New technique allows fast printing of microscopic electronics

|

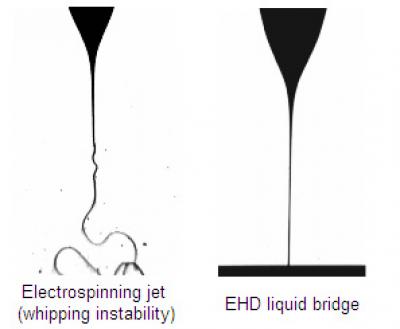

| Left: A conventional electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet -- a stream of electrically charged liquid forced from a nozzle -- which whips uncontrollably. Right: A stabilized jet produced by Princeton University engineers. The long-sought achievement has many possible uses in electronics and other industries.

Credit: Princeton University |

Abstract:

A new technique for printing extraordinarily thin lines quickly over wide areas could lead to larger, less expensive and more versatile electronic displays as well new medical devices, sensors and other technologies.

Fine print: New technique allows fast printing of microscopic electronics

Princeton, NJ | Posted on January 25th, 2008Solving a fundamental and long-standing quandary, chemical engineers at Princeton developed a method for shooting stable jets of electrically charged liquids from a wide nozzle. The technique, which produced lines just 100 nanometers wide (about one ten-thousandth of a millimeter), offers at least 10 times better resolution than ink-jet printing and far more speed and ease than conventional nanotechnology.

"It is a liquid delivery system on a micro scale," said Ilhan Aksay, professor of chemical engineering. "And it becomes a true writing technology."

Aksay and graduate student Sibel Korkut published the results Jan. 25 in Physical Review Letters. The paper also includes as a co-author Dudley Saville, a chemical engineering professor who initiated the project but died in 2006. The research was funded by grants from the Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Developing a deep understanding of the fundamental physics behind the process rather than building highly specialized equipment, the researchers were able to use a nozzle that is half a millimeter wide, or 5,000 times wider than the lines it produced.

The key to the process is something called an "electrohydrodynamic (EHD) jet" -- a stream of liquid forced from a nozzle by a very strong electric field. Such jets were first investigated in 1917 and are now commonly used in a variety of industrial processes. However, one of the main features of EHD jets is that the stream of liquid becomes unstable soon after it leaves the nozzle and either whips around uncontrollably or breaks up into fine liquid drops. Engineers have used these effects to their advantage in spinning fibers and in industrial electrospray painting, but the reason for the whipping instability, and thus any hope of stopping it, has been a long-standing problem.

In the early part of this decade, two researchers working independently -- Princeton graduate student Hak Poon and Cornell University physicist Harold Craighead -- found that the jet was stable for a very short distance after leaving the nozzle, but the result was still not practical and the reasons were still elusive.

"To understand how to control the jet in any engineering application we had to understand why this was happening," Aksay said.

Korkut took up the challenge and worked for nearly six years to nail down the mechanisms at play. In the end, she found that a key factor was that the liquid jet was transferring some of its electrical charge to the surrounding gas, which breaks into charged particles and carries some of the electrical current. Korkut's predecessors and other scientists had looked only at the density of the electrical charges on the surface of the liquid jet.

Expanding her view of the system led Korkut to a simple way to control the stability of the jet by changing the gas and the amount of water vapor. She was able to produce an extremely straight and stable jet more than 8 millimeters from the nozzle. (See video image of straight and whipping jets here: www.princeton.edu/~cml/html/EHDPself-assembly.html.)

The result is highly practical not only because of the fineness of the stream but also because the large size of the nozzle and the distance from the nozzle to the printed surface will prevent clogs or jams.

Aksay said a chief use for the technique could be in printing electrically conducting organic polymers (plastics) that could be the basis for large electronic devices. Conventional techniques for making wires of that size (100 nanometers) require laboriously etching the lines with a beam of electrons, which can only be done in very small areas. The new technique can lay down lines at the rate of meters per second as opposed to millionths of a meter per second.

Another application would be to use a liquid that solidifies into a fiber for making precise three-dimensional lattices. Such a product could be used as a scaffold to promote blood clotting in wounds and in other medical devices.

Princeton University has filed for a patent on the discovery and has licensed rights to Vorbeck Materials Corp., a specialty chemical company based in Maryland.

"Electronics is a huge potential application for this discovery," said John Lettow, president of Vorbeck and a 1995 chemical engineering alumnus of Princeton. "The printing technique could greatly increase the size of video displays and the speed with which high performance displays are made." Lettow said the technique also could be used in creating large sensors that collect information over a wide area, such as a sensor printed onto an airplane wing to detect metal fatigue.

For Korkut, publishing the results in the premier physics journal marks a gratifying conclusion to years of painstaking work that offered no guarantee of a practical answer. "You are digging into a hole and you don't know if you will hit the bottom," Korkut said. "You could just keep on digging."

Even though she began to see improved stability of the jet after five years, she still did not have a precise handle on the causes. Aksay and Saville pressed her to have a deeper understanding before publishing the results.

"It took more than a year after we saw the clues. We had to look at many possibilities," Korkut said.

Aksay said Korkut succeeded because of her persistence. "If you give up too soon, you can't come up with a breakthrough."

####

About Princeton University, Engineering School

The School of Engineering and Applied Science at Princeton, like the University itself, is unique in combining the strengths of a world-leading research institution with the qualities of an outstanding liberal arts college. Princeton Engineering conducts about $50 million a year in research funded by government agencies and industry in areas ranging from biological sensors to aerospace engineering to next-generation Internet design. At the same time, every faculty member – from new professors to Nobel laureates – teaches undergraduate and graduate students. The school also is proud of the many humanities majors and other non-engineers who choose to take its numerous courses that connect technical subjects with business, history, public policy, entrepreneurship and the arts.

In both its teaching and research, Princeton Engineering reaches beyond pure technical achievement and incorporates a broad understanding of the social, economic and cultural context that drives and is driven by technology. The school places a high value on harnessing the combined viewpoints of many academic disciplines and personal backgrounds to solve real-world problems. It educates students who become leaders not just in technical fields, but in all areas of public service, business, law and medicine. Princeton engineers have close interactions with the University’s world-class basic science departments, such as physics, biology and geosciences, as well as with Princeton faculty in public policy, economics, music, architecture and other fields.

For more information, please click here

Contacts:

Steven Schultz

609-258-3617

Copyright © Princeton University, Engineering School

If you have a comment, please Contact us.Issuers of news releases, not 7th Wave, Inc. or Nanotechnology Now, are solely responsible for the accuracy of the content.

| Related News Press |

News and information

![]() Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

Simulating magnetization in a Heisenberg quantum spin chain April 5th, 2024

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

![]() Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Good as gold - improving infectious disease testing with gold nanoparticles April 5th, 2024

Display technology/LEDs/SS Lighting/OLEDs

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

![]() Light guide plate based on perovskite nanocomposites November 3rd, 2023

Light guide plate based on perovskite nanocomposites November 3rd, 2023

![]() Simple ballpoint pen can write custom LEDs August 11th, 2023

Simple ballpoint pen can write custom LEDs August 11th, 2023

Sensors

Discoveries

![]() Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

Chemical reactions can scramble quantum information as well as black holes April 5th, 2024

![]() New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

New micromaterial releases nanoparticles that selectively destroy cancer cells April 5th, 2024

![]() Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Utilizing palladium for addressing contact issues of buried oxide thin film transistors April 5th, 2024

Announcements

![]() NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

NRL charters Navy’s quantum inertial navigation path to reduce drift April 5th, 2024

![]() Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

Discovery points path to flash-like memory for storing qubits: Rice find could hasten development of nonvolatile quantum memory April 5th, 2024

|

|

||

|

|

||

| The latest news from around the world, FREE | ||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Premium Products | ||

|

|

||

|

Only the news you want to read!

Learn More |

||

|

|

||

|

Full-service, expert consulting

Learn More |

||

|

|

||